For thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans, Native Americans inhabited what is today Charlestown. Their lives were centered around hunting, fishing and agriculture, which they carried out in all parts of Charlestown. Native Americans continued to play a substantial role in local affairs during the ensuing historical period. Their heritage lives on in the continuing presence of the Narragansett – their lands, institutions and historic sites that are still in tribal use.

One of the first written records of European contact in Charlestown dates back as early as the 1630s, when Col. John Mason marched to Connnecticut to fight the Pequots and stopped for the night at what was known as Ninigret’s Fort. Evidence of Dutch trading with the Niantic at Fort Ninigret dates to the early 1600s, and archaeological research suggests this site was in use as early as 700 AD.

In 1660, a private company organized in Newport purchased the land known as Misquamicoke (Misquamicut) from the well-respected Indian Sachem, Socho. The agreement was called the Misquamicut Purchase. The land was comprised of the present-day towns of Westerly, Charlestown, Richmond and Hopkinton. By 1669, the Town of Westerly was incorporated, and included the same four towns, becoming the fifth oldest town in the state.

At that time, there were only about thirty families in the entire area. Jeffrey Champlin, one of the original Misquamicut settlers, acquired a large tract of land in Charlestown, on which the Naval Air Station was later located. The Stantons also acquired large landholdings. Robert Stanton was one of the Misquamicut purchasers. Thomas Stanton had a trading post on the Pawcatuck River and set up a post in Quonochontaug around that time as well. A few of these earlier homes still stand.

The era of large plantations had begun and they were prosperous until around the time of the Revolutionary War, which caused their demise. The more northern plantations were generally livestock, dairy and the raising of Narragansett Pacers, a horse much in demand in the southern colonies. The Champlins, on their 2,000-acre plantation, specialized in sheep production. Reportedly, Joseph Stanton’s “lordship” in Charlestown consisted of a four-and-a-half mile tract on land containing 40 horses and as many slaves. The average coastal farm was said to have about 200 acres of cropland and pasture and up to 100 acres of woodland.

In 1738, Charlestown separated from the town of Westerly and was named in honor of Charles II, the English King who had granted Rhode Island its charter. Brought on primarily by the hardship to citizens traveling to attend town meetings and gatherings, the separation was finally passed, although not without much debate. At that point in time, Richmond was still part of Charlestown and would not separate until 1747.

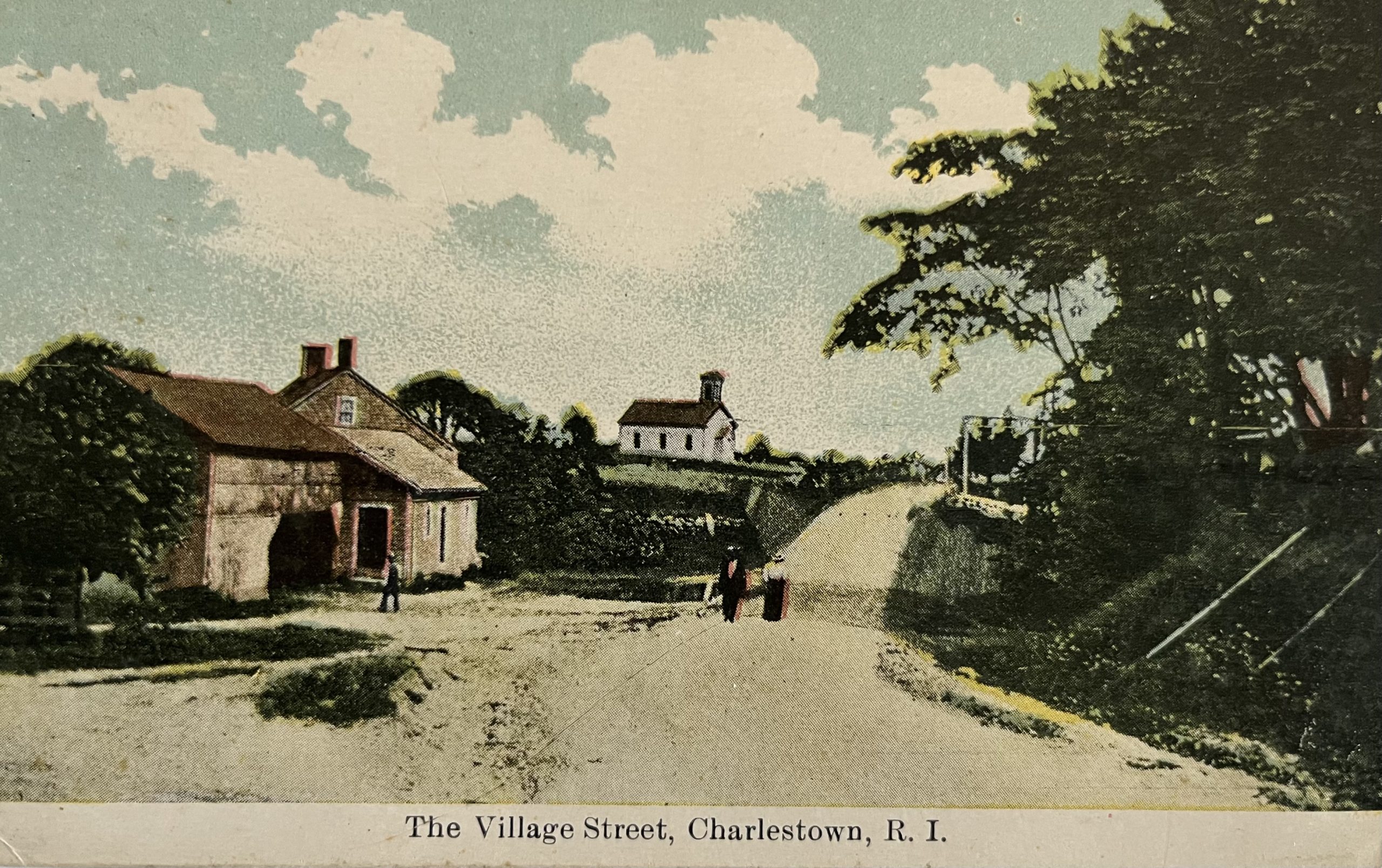

A young, colonial Charlestown was active and prosperous with its many mills, farms and coastal environment. The establishment of the Old Post Road along its seaboard had become a well-traveled route, thankfully as a result of its presence as a Native American trail thousands of years old. It now served as a means of communication and commerce within the colonies. Charlestown would go through many growing pains over the next 300 years, along with the rest of Rhode Island’s early towns, but retained its diversity, cultural heritage and its rich history.

In 1802, Joseph Nichols dammed the Pawcatuck River and built a grist mill near the present location of Carolina Mill, and for a time, the area was called “Nichols’ Mill.” At that time, the only buildings were the grist mill, a few small houses and outbuildings nearby. There also existed a bridge, known as “Nichols’ Bridge”.

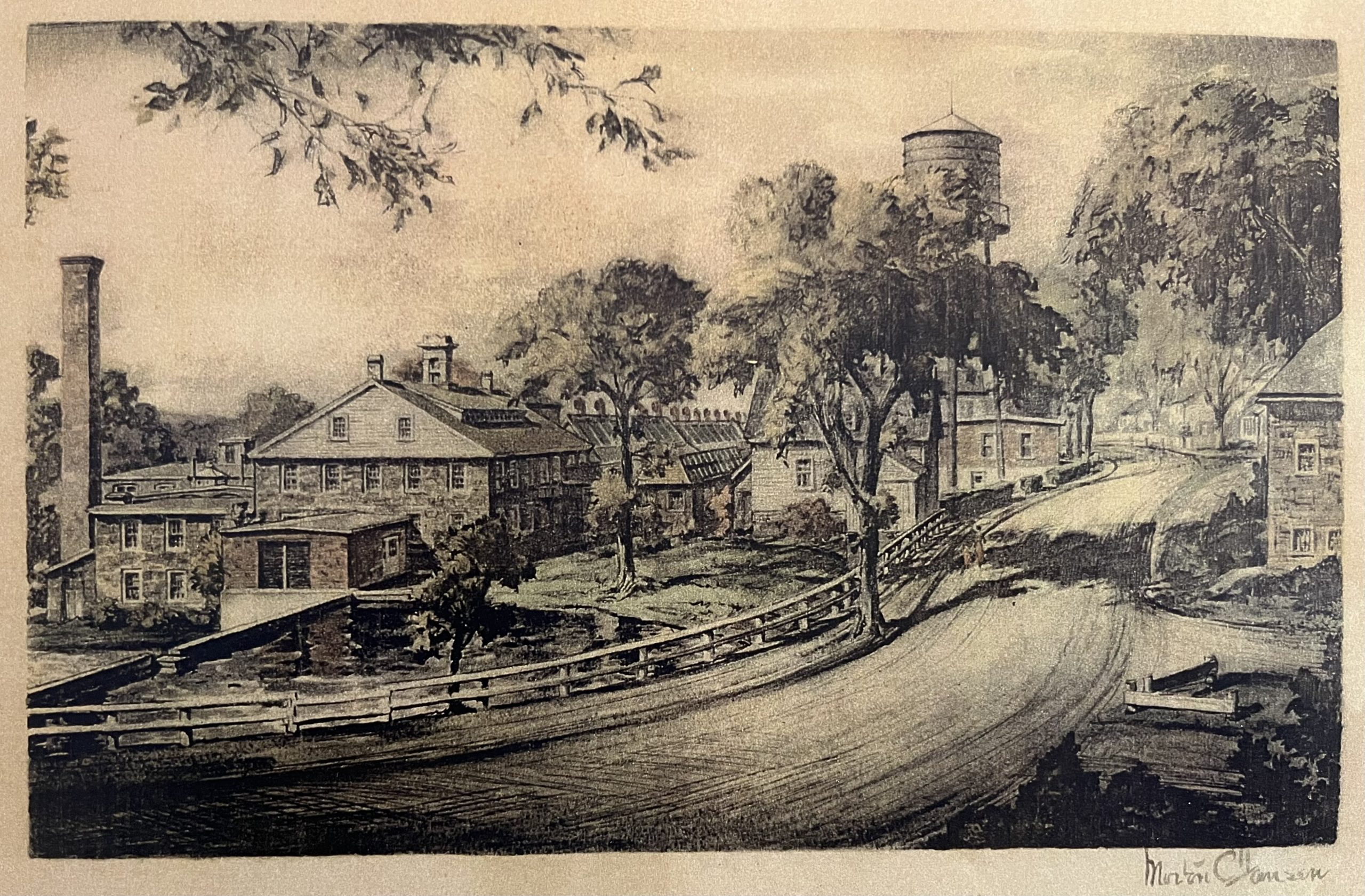

The grist mill was replaced by a textile mill for cotton goods in the mid-1830s, but was not successful until it became the property of Rowland G. Hazard of Peace Dale, South Kingstown in 1841, and was run as a woolen mill. By 1840, the Providence and Stonington railroad was built, making it economically feasible for factories to be built on the river. Mr. Hazard assembled 1,000 acres of land on the Nichols’ grist mill site and built a dam, a mill pond and a larger cotton mill. He also built a mill town that he named Carolina, after his wife, Caroline Newbold Hazard.

Mr. Hazard was a brilliant business man. He was also a social visionary active in social justice issues throughout his life. Carolina was consciously designed to be a model mill town with a school, good housing, clean water, a church and social organizations. From 1840 to 1870, about two thirds of the houses in Carolina were built by people who lived and worked in this thriving village, names familiar in the Cross’ Mills and Quonochontaug areas.

In 1868, Hazard sold the mill to Ellison Tinkham and Franklin Metcalf, who also proved to be good businessmen, as well as good people to work for. The Carolina Mill thrived and so did the village. Employment was steady and social life was busy. Music and theater, baseball and expeditions to the beaches were frequent. There were also a wide variety of small businesses in town: a cigar factory, for example, operated for years. The factory was owned and operated by William D. Cross, a direct descendant of Joseph Cross, founder of Cross’ Mills, and who with his son and grandson, were tax collectors of Charlestown for many years.

By the 1890s, the name Carolina Mills had become Carolina. Edward C. Brown had built a good-sized store which became highly patronized under the name of “Edward C. Brown and Sons.” Mr. Brown and his son traveled all over the Charlestown area by horse and wagon delivering meat and groceries. By 1932, Linton L. Brown operated his grandfather’s business and was elected to the office of Charlestown Town Clerk. The office was located in the old store. Linton served faithfully and well as the town clerk for the next forty years.

During the early 1900s, the village fell on hard times. Over-expansion during the 1920’s, the Depression and the departure of the textile businesses for the south, and then the Hurricane of 1938, left the town with little to keep it going except Wright’s Garage and strong families. In the 1970s, Rt. 95 made it accessible to newcomers and the village began to grow again to the present day. It has survived remarkably intact and it is much as it was when it was created in 1840.

The history of this village began many years before European contact, as it was part of a well-traveled passage of the Native Americans. These prehistoric paths along the coast eventually became the foundation of the Old Post Road around 1703, which provided for the establishment and commerce of Cross’ Mills.

With the ancient site of Fort Ninigret just 1/4 mile to the southwest on the ‘Pequot Trail’, one of the earliest written records in existence of this area was made by Capt. John Mason during his famous march from Narragansett Bay on his way to Connecticut to fight the Pequots in 1637. However, there are references to an earlier date relative to Dutch and Indian trade dating as far back as the late 1500’s to early 1600’s at this site. Here, then, lived the Niantics, subsidiary to the larger Nahahiggansick (Narragansett) Tribe to the Northeast.

By the late 1600’s, this village, though sparse of homes, was an established community. Many who settled here were listed as ‘freemen’ in ‘Misquamocuck’ (Misquamicut), of which present day Charlestown was then a part of. Cross’ Mills was the only village between Westerly and Tower Hill for many years.

The Village derived its name from the Cross family, one of Charlestown’s founding families, who immigrated here from Scotland. Joseph Cross, son of original settler, John Cross, purchased the mill in 1709. Historian William Franklin Tucker, in his “Historical Sketch of the Town of Charlestown in RI, from 1636 to 1876”, writes regarding the mill …

“The first information relating to a grist mill is found on record in Sachem Ninigret’s deed to the colony, dated March 28, 1709. This mill then belonged to Joseph Davill and was in good working condition at that time. It was located on the brook at Cross’ Mills, where the present one stands; but I am unable to find in my present researches, the exact date when the mill was first built. This is the only grist mill in the town, and Peleg Cross and his heirs have held possession of it for a long time…”

For the next 300 years, the Cross Family held positions of community and government leadership. The village became the center of town with a grist mill, postal service, blacksmith, store and eventually a school, church and meeting hall, and provided a stopping point for weary travelers as well as many statesmen making their way north to Providence or Boston along the Old Post Road.

As early as 1772, a saw mill and iron manufactory were operating here along the Pawcatuck River. On May 3, 1820, Lewis Kenyon purchased a large farm from Thomas Holburton. He set up a mill to card and weave fibers where the village of Kenyon is now located and the area became known as Holburton’s Mills. Lewis descended from John Kenyon, who settled in Misquamicut in the 1660’s as a “freeman.” His father lived in Charlestown and fought in the Revolutionary War under Capt. Amos Green of Charlestown.

The purchase included a small stone woolen mill. Here, Lewis established and ran a business of finishing cloth until his death in 1839. Elijah Kenyon, his son, carried on the mill business, eventually forming a partnership with his brother, Abial. By that time, the old mill was used for carding and spinning. The first six looms were introduced for the weaving of cloth. These six looms brought much success to the mill.

In 1844, a new, much larger mill was built near the site of the old mill with greater facilities for manufacturing. By 1856, Elijah purchased the interest of his brother, Abial, and successfully operated the mill until 1863. That same year, C.B. Coon was admitted as a partner and a large, spacious store was added for the convenience of the mill workers. The village by then was called Kenyon’s Mills.

In 1881, the new post office was added to the village and the name was finally changed to Kenyon. Another change came that same year when Elijah died and his son, John, succeeded to the business and operated it with great success under the name E. Kenyon & Son. By 1889, a railroad station was established along the main line of the New York, Providence and Boston railroad which passes through the village.

As we have seen with each mill village, a pattern of progression emerges. Each used the power of the Pawcatuck River. Every mill builder and owner built good white clapboard houses for his workers. Thus a neat, orderly village emerged with a school, store and church. Between 1850-1900, many workers came from the terrible textile villages of England where working conditions were unspeakable, bringing to our villages people of an industrious nature. As these mills grew in size with prosperity, so did the villages.

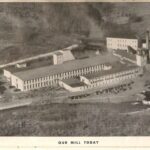

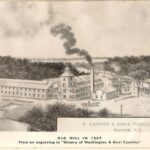

Below are some images from the Kenyon Mill pamphlet.

Among the wooded hills and winding Pawcatuck River in the northern part of Charlestown is the small, former manufacturing center of Shannock, shared with the Town of Richmond on the river’s opposite bank. The houses and various structures are sited close to the street line with white picket fences, mature trees and stone walls. Shannock owes its existence to the upper and lower falls on the river, where in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries several saw, grist and woolen mills were established. These were small operations serving only the local area.

Shannock’s first two mills appear to have been saw mills at the upper falls, today’s Horseshoe Falls. These mills existed before 1759, when they were willed by Jeffrey Babcock to his son Abraham, and may have been in use as early as the 1730’s. In 1771, Joshua Clarke bought the two mills and soon added a woolen mill nearby where he manufactured blankets for the colonists fighting in the American Revolution. Other early mills nearby included a saw mill erected before 1815 on the upper side of upper falls and a grist mill at the lower falls, operated by Jesse Wilcox in 1828.

The real growth of manufacturing in Shannock took place with the construction of the New York, Providence and Boston Railroad through the area in 1837. The railroad, which became part of the “Shore Line” from New York to Boston in 1858, passed through the village, permitting the economical shipment of raw materials and finished goods.

With the coming of the railroad, larger factories were constructed on both falls. John T. Knowles built a cotton and woolen mill on the lower falls. It was subsequently enlarged by George Weeden and sold in 1875 to A. Carmichael and Co. The Carmichaels built a beautiful estate called “Riverview” on the Charlestown side of the village overlooking the river on the hill where in 1636, years before the colonists had established themselves in the area, the Narragansett and Pequot Indians fought a fierce battle for fishing rights.

However, it was the Clark(e) family that had the largest impact on Shannock. Along with the early mills begun by Joshua Clark and his son, Perry, Simeon Clark constructed a large stone mill in 1848, powered by the Horseshoe Falls, where he developed the manufacture of cotton yarn. Eventually the factory was expanded and mill worker housing, stores and a community hall were constructed. In 1918, the Clarks built a model village, Columbia Heights, for their workers. Constructed on the old Card farm in Charlestown, it was hailed for its innovative design in providing modern worker housing on a level never before seen.

Simeon’s son, George Herbert Clark, along with his son, George Perry Clark, continued the operation under the name Columbia Narrow Fabrics Co., until it closed in 1967. Five generations of the Clarks and their families were instrumental in the evolution of this unique South County village, which today still exhibits much of the original visual appeal of the past.

A fine collection of historical photos of Shannock Village is available on driftways.com.

The coastal habitat of Quonochontaug provided a summer home for the people of the Niantic Tribe for thousands of years. It shaped daily life with an abundance of shellfish, seaweed for farming and a cooler home during the summer months, as it did along all of Charlestown’s coastal ponds. Its rocky shore, however, proved hazardous for ships, and eventually the Quonochontaug Life Saving Station was established in 1892.

In 1659, Thomas Stanton settled here to establish a trading post and was given a large tract of land by the Sachem Ninigret, called “Quonocontoge Neck.” Legend has it that the gift was in exchange for the safe return of an Indian princess. The Stantons prospered, as did other early families in this area, such as the Sheffields, Babcocks, Pendletons and Champlins, and developed large farmlands, known as plantations. Slavery was not uncommon on these farmlands with the onset of war between local Native Indians and colonial expansion, and both the Indians and the West African slave trade provided the means for working these farms.

During the 1700s, Thomas Stanton’s farm, as well as other family farms, were divided between the growing generations. By the 1800s, they had been divided again into smaller lots and eventually the area became more populated. By the mid-to late-1800s, boarding houses, hotels and cottages were built along the breachway and shoreline, providing a respite for local folks and mill workers escaping from the summer heat.

In 1881, Quonochontaug became the site of an iron mining operation financed by Thomas A. Edison, in which iron was separated from the sand with magnets. Ultimately, the venture ended when it was realized that less expensive iron was available elsewhere.

By the end of the 1800s, “Quonnie” had become a busy and fashionable resort. It remained popular until the Great Hurricane of 1938, which brought tremendous devastation to this community. Eventually, the area experienced a resurgence of summer and year-round residences. Today, some of the oldest historic homes still stand.